What Is DNS and How to Look Them Up

Reference:

About DNS

What’s DNS

The Domain Name System (DNS), is the phonebook of the internet. Humans interact with internet via domain names (like “www.example.com”), while browsers interact through Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. DNS translates domain names to IP addresses so taht browers could load the resources.

Each device connected to the internet has an unique IP associated with it, for which could be used to find this device on the internet. DNS servers provide look-ups for the IP addresses and eliminate the need for humans to memorize IP addresses.

DNS Servers

What is DNS Server

Machines dedicated to answering DNS queries (Domain Name -> IP).

4 Types DNS Servers

In a typical DNS query without any caching, there are four servers that work together to deliver an IP address to the client: recursive resolvers, root nameservers, TLD nameservers, and authoritative nameservers.

DNS Recursor

The recursor (also referred to as the DNS recursive resolver) can be thought of as a librarian who is asked to go find a particular book in the library.

The DNS recursor is a server designed to receive queries from client machines through applications such as web browsers. Typically the recursor is then responsible for making additional requests to satisfy the client’s DNS query.

DNS recursive resolvers such as Google DNS, OpenDNS, and providers like Comcast all maintain data center installations of DNS recursive resolvers. These resolvers allow for quick and easy queries through optimized clusters of DNS-optimized computer systems.

Root Nameserver

The (13) root server is the first step in translating domain names to IP addresses. It can be thought of like an index in a library that points to different racks of books - typically it serves as a reference to other more specific locations.

A root server accepts a recursive resolver’s query which includes a domain name, and the root nameserver responds by directing the recursive resolver to a TLD nameserver, based on the extension of that domain (.com, .net, .org, etc.).

The root nameservers are overseen by a nonprofit called the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). Note that while there are 13 root nameservers, that doesn’t mean that there are only 13 machines in the root nameserver system. There are 13 types of root nameservers, but there are multiple copies of each one all over the world.

TLD Nameserver

The top level domain server (TLD) can be thought of as a specific rack of books in a library. This nameserver is the next step in the search for a specific IP address.

A TLD nameserver maintains information for all the domain names that share a common domain extension, such as .com, .net, or whatever comes after the last dot in a url. For example, a .com TLD nameserver contains information for every website that ends in ‘.com’. If a user was searching for google.com, after receiving a response from a root nameserver, the recursive resolver would then send a query to a .com TLD nameserver, which would respond by pointing to the authoritative nameserver for that domain.

Management of TLD nameservers is handled by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), which is a branch of ICANN. The IANA breaks up the TLD servers into two main groups:

- Generic top-level domains: These are domains that are not country specific, some of the best-known generic TLDs include .com, .org, .net, .edu, and .gov.

- Country code top-level domains: These include any domains that are specific to a country or state. Examples include .uk, .us, .ru, and .jp

Authoritative nameserver

This final nameserver can be thought of as a dictionary on a rack of books, in which a specific name can be translated into its definition.

The authoritative nameserver is the last stop in the nameserver query. It contains information specific to the domain name it serves (e.g. google.com) and it can provide a recursive resolver with the IP address of that server found in the DNS A record, or if the domain has a CNAME record (alias) it will provide the recursive resolver with an alias domain, at which point the recursive resolver will have to perform a whole new DNS lookup to procure a record from an authoritative nameserver (often an A record containing an IP address).

Additional nameserver

It’s worth mentioning that in instances where the query is for a subdomain such as foo.example.com or blog.cloudflare.com, an additional nameserver will be added to the sequence after the authoritative nameserver, which is responsible for storing the subdomain’s CNAME record.

What are the steps in a DNS lookup?

For most situations, DNS is concerned with a domain name being translated into the appropriate IP address. To learn how this process works, it helps to follow the path of a DNS lookup as it travels from a web browser, through the DNS lookup process, and back again. Let’s take a look at the steps.

Note: Often DNS lookup information will be cached either locally inside the querying computer or remotely in the DNS infrastructure. There are typically 8 steps in a DNS lookup. When DNS information is cached, steps are skipped from the DNS lookup process which makes it quicker. The example below outlines all 8 steps when nothing is cached.

The 8 steps in a DNS lookup:

- A user types ‘example.com’ into a web browser and the query travels into the Internet and is received by a DNS recursive resolver.

- The resolver then queries a DNS root nameserver (.).

- The root server then responds to the resolver with the address of a Top Level Domain (TLD) DNS server (such as .com or .net), which stores the information for its domains. When searching for example.com, our request is pointed toward the .com TLD.

- The resolver then makes a request to the .com TLD.

- The TLD server then responds with the IP address of the domain’s nameserver, example.com.

- Lastly, the recursive resolver sends a query to the domain’s nameserver.

- The IP address for example.com is then returned to the resolver from the nameserver.

- The DNS resolver then responds to the web browser with the IP address of the domain requested initially.

Recursive DNS Resolver vs Recursive DNS Query

What is a DNS resolver?

The DNS resolver is the first stop in the DNS lookup, and it is responsible for dealing with the client that made the initial request. The resolver starts the sequence of queries that ultimately leads to a URL being translated into the necessary IP address.

What is a DNS Query?

A DNS query (also known as a DNS request) is a demand for information sent from a user’s computer (DNS client) to a DNS server (typically a DNS recursive resolver).

What are the types of DNS Queries?

In a typical DNS lookup three types of queries occur. By using a combination of these queries, an optimized process for DNS resolution can result in a reduction of distance traveled. In an ideal situation cached record data will be available, allowing a DNS name server to return a non-recursive query. 3 types of DNS queries:

- Recursive query - a DNS client requires that a DNS server will respond to the client with either the requested resource record or an error message if the resolver can’t find the record.

- Iterative query - If the queried DNS server does not have a match for the query name, it will return a referral to a DNS server authoritative for a lower level of the domain namespace. The DNS client will then make a query to the referral address.

- Non-recursive query - typically this will occur when a DNS resolver client queries a DNS server for a record that it has access to either because it’s authoritative for the record or the record exists inside of its cache.

DNS Caching

What is DNS caching? Where does DNS caching occur?

The purpose of caching is to temporarily stored data in a location that results in improvements in performance and reliability for data requests. DNS caching involves storing data closer to the requesting client so that the DNS query can be resolved earlier and additional queries further down the DNS lookup chain can be avoided, thereby improving load times and reducing bandwidth/CPU consumption. DNS data can be cached in a variety of locations, each of which will store DNS records for a set amount of time determined by a time-to-live (TTL). This time limit is set explicitly in the DNS records for each site. Typically the TTL is in the 24-48 hour range. A TTL is necessary because web servers occasionally change their IP addresses, so resolvers can’t serve the same IP from the cache indefinitely.

Browser DNS caching

Modern web browsers are designed by default to cache DNS records for a set amount of time. the purpose here is obvious; the closer the DNS caching occurs to the web browser, the fewer processing steps must be taken in order to check the cache and make the correct requests to an IP address. When a request is made for a DNS record, the browser cache is the first location checked for the requested record.

Operating system (OS) level DNS caching

The operating system level DNS resolver is the second and last local stop before a DNS query leaves your machine. The process inside your operating system that is designed to handle this query is commonly called a “stub resolver” or DNS client. When a stub resolver gets a request from an application, it first checks its own cache to see if it has the record. If it does not, it then sends a DNS query (with a recursive flag set), outside the local network to a DNS recursive resolver inside the Internet service provider (ISP).

When the recursive resolver inside the ISP receives a DNS query, like all previous steps, it will also check to see if the requested host-to-IP-address translation is already stored inside its local persistence layer.

The recursive resolver also has additional functionality depending on the types of records it has in its cache:

- If the resolver does not have the A records, but does have the NS records for the authoritative nameservers, it will query those name servers directly, bypassing several steps in the DNS query. This shortcut prevents lookups from the root and .com nameservers (in our search for example.com) and helps the resolution of the DNS query occur more quickly.

- If the resolver does not have the NS records, it will send a query to the TLD servers (.com in our case), skipping the root server.

In the unlikely event that the resolver does not have records pointing to the TLD servers, it will then query the root servers. This event typically occurs after a DNS cache has been purged.

DNS Records

What is a DNS record?

DNS records (aka zone files) are instructions that live in authoritative DNS servers and provide information about a domain including what IP address is associated with that domain and how to handle requests for that domain. These records consist of a series of text files written in what is known as DNS syntax. DNS syntax is just a string of characters used as commands which tell the DNS server what to do. All DNS records also have a ‘TTL’, which stands for time-to-live, and indicates how often a DNS server will refresh that record.

What are the most common types of DNS record?

- A record - The record that holds the IP address of a domain.

- CNAME record - Forwards one domain or subdomain to another domain, does NOT provide an IP address.

- MX record - Directs mail to an email server.

- TXT record - Lets an admin store text notes in the record.

- NS record - Stores the name server for a DNS entry.

- SOA record - Stores admin information about a domain.

- SRV record - Specifies a port for specific services.

- PTR record - Provides a domain name in reverse-lookups.

A Record

The ‘A’ stands for ‘address’ and this is the most fundamental type of DNS record, it indicates the IP address of a given domain. For example if you pull the DNS records of google.com, the ‘A’ record currently returns an IP address of: 172.217.5.78. ‘A’ records only hold Ipv4 addresses, if the site has a Ipv6 address, it will instead use an ‘AAAA’ record

Example of an A record:

| example.com | record type | value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| @ | A | 12.34.56.78 | 14400 |

The ‘@’ here indicates that this is a record for the root domain, and the ‘14400’ value is the TTL (Time To Live), listed in seconds. The default TTL for A records is 14400 seconds. This means that if an A record gets updated, it takes 240 minutes (14400 seconds) to take effect (because after 14400 secs you will refetch).

The vast majority of websites only have one A record, but it’s possible to have several A records.

CNAME record

The ‘canonical name’ record is used in lieu of an A record, when a domain or subdomain is an alias of another domain. Imagine a scavenger hunt where each clue points to another clue, and the final clue points to the treasure. A domain with a CNAME record is like a clue which can point you to another clue (another domain with a CNAME record) or to the treasure (a domain with an A record). For example, suppose www.example.com has a CNAME record with a value of ‘example.com’ (without the ‘www’). This means when a DNS server hits the DNS records for www.example.com, it actually triggers another DNS lookup to example.com, returning example.com’s IP address. In this case we would say that example.com is the canonical name (or true name) of blog.example.com. All CNAME records must point to a domain, never to an IP address.

Oftentimes, when sites have subdomains such as blog.example.com or shop.example.com, those subdomains will have CNAME records which point to a root domain (example.com). This way if the IP of the host changes, only the DNS A record for the root domain needs to be updated and all the CNAME records will follow along with whatever changes are made to the root.

A frequent misconception is that a CNAME record must always resolve to the same website as the domain it points to, but this is not the case. The CNAME record only points the client to the same IP address as the root domain. Once the client hits that IP address, the web server will still handle the URL accordingly. So for instance, blog.example.com might have a CNAME that points to example.com, directing the client to example.com’s IP address. But when the client actually connects to that IP address, the web server will look at the URL, see that it’s blog.example.com, and deliver the blog page rather than the home page.

Example of a CNAME record:

| example.com | record type | value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| @ | CNAME | is an alias of example.com | 32600 |

In this example you can see that blog.example.com points to example.com, and assuming it’s based on our example A record we know that it will eventually resolve to the IP address 12.34.56.78.

MX record?

This is the ‘mail exchange’ record, and it directs email to a mail server. The MX record indicates how email messages should be routed in accordance with Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP, the standard protocol for all email.) Like CNAME records, an MX record must always point to another domain.

Example of an MX record:

| example.com | record type | value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| @ | MX | 10 mailhost.example.com | 45000 |

| @ | MX | 20 mailhost2.example.com | 45000 |

The numbers before the domains in the value entries for these MX records indicate preference; the server will always try mailhost1 first because 10 is lower than 20, in the result of a message send failure, the server will default to mailhost2.

DIG Command

Domain information groper (DIG) is a flexible tool for interrogating DNS name servers. It performs DNS lookups and displays the answers that are returned from the name server(s) that were queried.

With the dig command, you can query information about various DNS records including host addresses, mail exchanges, and name servers. It is the most commonly used tool among system administrators for troubleshooting DNS problems because of its flexibility and ease of use.

Dig Command Format

$ dig name @server type

dig invokes the utility

name is the host you are looking for information about (eg. example.com)

@server allows you to query the name from a different location (eg. 8.8.8.8 for Google’s resolver or dns1.p01.nsone.net to test a zone before you delegate)

type is an optional field that allows you to have DIG locate a specific record type (eg. A, AAAA, CNAME, MX, TXT, etc.)

Understanding the Dig Output

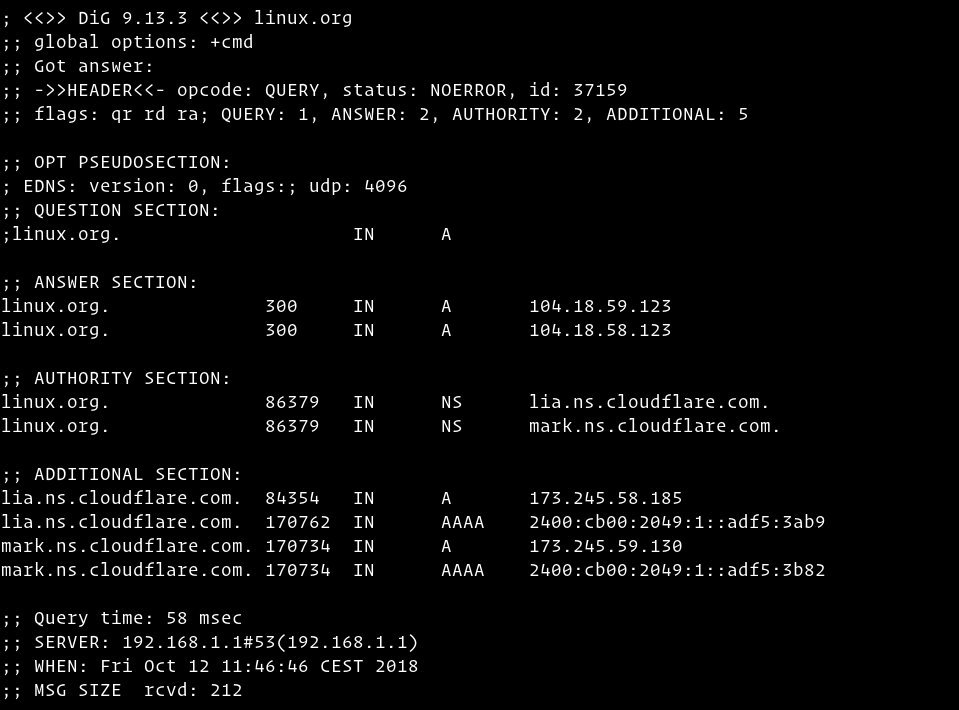

$dig linux.org

The output should look something like this:

- The first line of the output prints the installed dig version, and the query that was invoked. The second line shows the global options (by default only cmd).

; <<>> DiG 9.13.3 <<>> linux.org ;; global options: +cmdIf you don’t want those lines to be included in the output use the +nocmd option. This options must be the very first argument after the dig command.

- This section includes technical details about the answer received from the requested authority (DNS server). The second line of this section is the header, including the opcode (the action performed by dig) and the status of the action. In this case the status is NOERROR which means that the requested authority served the query without any issue. Next line starts out with flags - these are options that can be set to determine which sections of the answer get printed, or determine the timeout and retry strategies. The subsequent fields Query, Answer, Authority and Additional express the number of records in each section for all opcodes.

;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 37159 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 2, ADDITIONAL: 5The meaning of each flag:

qr = specifies whether this message is a query (0), or a response (1) aa = Authoritative Answer tc = Truncation rd = Recursion Desired (set in a query and copied into the response if recursion is supported) ra = Recursion Available (if set, denotes recursive query support is available) ad = Authenticated Data (for DNSSEC only; indicates that the data was authenticated) cd = Checking Disabled (DNSSEC only; disables checking at the receiving server) - This section is shown by default only on the newer versions if the dig utility. This is related to the Extension mechanisms for DNS (EDNS).

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION: ; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 4096 - The question section reaffirms what you went looking for. By default, dig will request the A record. In this case, DIG went looking for an IPv4 address (A Record) at linux.org.

;; QUESTION SECTION: ;linux.org. IN A - The answer section provides us with an answer to our question. The answer we’re looking at here has five parts: the NAME, TTL, CLASS, TYPE and RDATA.

linux.org. 300 IN A 104.27.167.219 linux.org. 300 IN A 104.27.166.219- NAME: The NAME resource field states the domain name to which the resource record refers.

- TTL: The TTL resource field is an abreviation for the phrase “time to live”. This field gives the amount of time, in seconds, for which the record should be considered valid.

- CLASS: The CLASS resource field is generally rarely used. The IN in this example, and most examples you’re likely to see, indicates that this record is of the “Internet” CLASS of DNS record. There are also CH (for Chaosnet) and HS (for Hesiod) classes, as well as QCLASS options for use only in queries.

- TYPE: The TYPE resource field is where the format of the record is defined. There are many TYPEs of resource records, the most common being A (which gives an IPv4 address for a NAME), AAAA (which gives an IPv6 address), MX (which sets the location of a mail server), CNAME (or canonical name, which maps one NAME to another), and TXT (which can include any arbitrary text). This field really defines what sort of RDATA is to be expected for the record.

- RDATA:The RDATA resource field is, in many ways, the heart of a DNS answer. Without it, there’s nothing for the record to do. In this particular case, since we’re looking at an A record, the RDATA is an IPv4 address which indicates where the NAME linux.org should resolve to. Other record TYPEs will have different RDATA content.

- The Authority section tells us what server(s) are the authority for answering DNS queries about the queried domain.

;; AUTHORITY SECTION: linux.org. 86379 IN NS lia.ns.cloudflare.com. linux.org. 86379 IN NS mark.ns.cloudflare.com. - The additional section gives us information about the IP addresses of the authoritative DNS servers shown in the authority section.

;; ADDITIONAL SECTION: lia.ns.cloudflare.com. 84354 IN A 173.245.58.185 lia.ns.cloudflare.com. 170762 IN AAAA 2400:cb00:2049:1::adf5:3ab9 mark.ns.cloudflare.com. 170734 IN A 173.245.59.130 mark.ns.cloudflare.com. 170734 IN AAAA 2400:cb00:2049:1::adf5:3b82 - This is the last section of the dig output which includes statistics about the query.

;; Query time: 58 msec ;; SERVER: 192.168.1.1#53(192.168.1.1) ;; WHEN: Fri Oct 12 11:46:46 CEST 2018 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 212

Query a Short Answer

$ dig linux.org +short

Output:

104.18.59.123

104.18.58.123

Query a Detailed Answer

For more detailed answer turn off all the results using the +noall options and then turn on only the answer section with the +answer option.

$ dig linux.org +noall +answer

Output:

; <<>> DiG 9.13.3 <<>> linux.org +noall +answer

;; global options: +cmd

linux.org. 67 IN A 104.18.58.123

linux.org. 67 IN A 104.18.59.123

Query Specific Name Server

By default if no name server is specified, dig will use the servers listed in /etc/resolv.conf file.

To specify a name server against which the query will be executed use the @ (at) symbol followed by the name server IP address or hostname.

$ dig linux.org @8.8.8.8

Output:

; <<>> DiG 9.13.3 <<>> linux.org @8.8.8.8

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 39110

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 512

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;linux.org. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

linux.org. 299 IN A 104.18.58.123

linux.org. 299 IN A 104.18.59.123

;; Query time: 54 msec

;; SERVER: 8.8.8.8#53(8.8.8.8)

;; WHEN: Fri Oct 12 14:28:01 CEST 2018

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 70

Query A Record Type

To get a list of all the address(es) for a domain name use the a option:

$ dig +nocmd google.com a +noall +answer

output:

google.com. 128 IN A 216.58.206.206

Query CNAME Records

$ dig +nocmd mail.google.com cname +noall +answer

output:

mail.google.com. 553482 IN CNAME googlemail.l.google.com.

Reverse DNS Lookups

To query the hostname associated with a specific IP address use the -x option.

$ dig -x 208.118.235.148 +noall +answer

As you can see from the output below the IP address 208.118.235.148 is associated with the hostname wildebeest.gnu.org

; <<>> DiG 9.13.3 <<>> -x 208.118.235.148 +noall +answer

;; global options: +cmd

148.235.118.208.in-addr.arpa. 245 IN PTR wildebeest.gnu.org.

Bulk Queries

If you want to query a large number of domains, you can add them in a file (one domain per line) and use the --f option followed by the file name.

In the following example, we are querying the domains listed in the domains.txt file.

lxer.com

linuxtoday.com

tuxmachines.org

Run:

dig -f domains.txt +short

Output:

108.166.170.171

70.42.23.121

204.68.122.43

Checking to see if a DNS server has a particular RR in its cache

“RR” stands for resource record, which is DNS-speak for any kind of record (A, CNAME, SOA, NS, PTR, etc.). If you want to infer whether anyone using a particular DNS server has visited a host recently, you can specify a non-recursive query. Most DNS servers will obey this request, although this is not required. For security reasons some better DNS server software can be configured to intentionally ignore requests not to recurse.

$ dig @8.8.8.8 uploads.spy2mobile.com +norecurse

Show the version of BIND

Today the CH class is misused by BIND, for the following neat tricks:

$ dig -t txt -c chaos version.bind @9.9.9.9

;; ANSWER SECTION:

version.bind. 86400 CH TXT "Q9-P-6.0"

$ dig CHAOS TXT id.server @1.1.1.1

;; ANSWER SECTION:

id.server. 0 CH TXT "LAX"

Other DNS servers, for example, OpenDNS, does not support it, but they have their own custom domain for debugging:

$ dig -t TXT debug.opendns.com @208.67.222.123

;; ANSWER SECTION:

debug.opendns.com. 0 IN TXT "server m51.lax"

debug.opendns.com. 0 IN TXT "flags 40020 0 70 180000000000000000003950800780000000000"

debug.opendns.com. 0 IN TXT "originid 0"

debug.opendns.com. 0 IN TXT "actype 0"

debug.opendns.com. 0 IN TXT "source 137.110.56.85:50582"

Related reading: HOW TO FIND YOUR CLOSEST ANYCAST DNS SERVER WITH DIG

Figuring out which Google DNS Cluster you are using

$ dig o-o.myaddr.l.google.com -t txt +short @8.8.8.8

"173.194.94.135" <<<<<<DNS Server IP, reference the list above to get the cluster, Council Bluffs, IA

"edns0-client-subnet 207.xxx.xxx.0/24" <<<< Your Source IP Block

Relevant readings: